Archives - Page 2

-

Orders in Architecture. Vitruvius's Migration (eng)

Vol. 4 No. 7 (2015)Author (edited by): Ludovico Micara

After the L'ADC n.6/2015 "ORDERS IN ARCHITECTURE. Do Architectural Forms Have a Meaning?" L'ADC launches a second call for papers on the issue ORDERS IN ARCHITECTURE. Vitruvius' Migrations edited by Ludovico Micara.

-

Gli Ordini in architettura. Le forme architettoniche significano? (ita)

Vol. 3 No. 6 (2015)ORDERS IN ARCHITECTURE. Do Architectural Forms Have a Meaning?

The issue of the "orders" in architecture covers an extremely vast field of theories, studies and design experiences that have all been developed in the framework of the architectural thinking of the Western tradition.

The classical architectural orders established a stylistic canon, a code, and a language as well, in order for architectures to speak, to transmit and to signify.

Generally speaking, the core issue is the creation of meanings through architecture.

In this view, a major vehicle of sense has not just been the experience of architectural orders, but rather their transgression, their variation, up to the extreme end of disorder. Following Ludovico Quaroni, “The Greeks, the Etruscans, the Romans, the architects of the Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque, Classicism made use of the orders to design as many architectures, and these were different, and even opposite one versus the other”….“The orders were only components of the architectural design, that is, elements drawn from manuals that could be used and transformed in relation to the various syntactic contexts”1.

The issue of the architectural orders is therefore a partial answer to a broader question, skillfully phrased in 1886 by the twenty-two years old Heinrich Wölfflin in the introduction to Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur2, his inaugural dissertation at the Faculty of Philosophy of Munich University: How it is possible that architectural forms are an expression of soul, of a Stimmung?

Therefore, the question is: is it still possible today to refer to the communicative resources of the architectural orders for creating meanings through architecture?1 L. Quaroni, Progettare un edificio. Otto lezioni di architettura, Gabriele Mazzotta editore, Milano 1977, p. 215.

2 H. Wölfflin, Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur, 1886. French edition: Wölfflin, Prolégomènes à une psychologie de l’architecture, introduction by Bruno Queysanne, Editions Carré, 1996.

GLI ORDINI IN ARCHITETTURA. Le forme architettoniche significano?Il tema degli "ordini" in architettura copre un campo vastissimo di teorie, studi ed esperienze progettuali, declinate prevalentemente nel pensiero architettonico della tradizione occidentale.

Ma gli ordini architettonici classici hanno costituito anche un canone, un codice e un linguaggio perché l’architettura parlasse, si trasmettesse e producesse significati.Quello che qui veramente interessa è la ricerca di produzione di significato attraverso l’architettura.

In questo senso gli ordini, ma soprattutto la loro trasgressione o variazione, sono state uno strumento fondamentale. Cito Ludovico Quaroni: “Gli ordini sono serviti ai Greci, agli Etruschi, ai Romani, ai romanici, agli architetti del Rinascimento, del barocco, del classicismo per fare altrettante architetture, una diversa dall’altra, una in opposizione, spesso, all’altra”. E ancora: gli ordini “erano solo ‘componenti’ delle progettazione, cioè elementi che si prendevano pari pari dal manuale per usarli poi in modo del tutto libero, in quei contesti sintattici, di cui i manuali non hanno mai parlato, ovvero erano elementi che si prendevano per lavorarci sopra e trasformarli così in una cosa diversa da quella che ‘insegnava’ il manuale”1.

Il tema degli “ordini”, quindi, è una risposta parziale ad una domanda molto più ampia magistralmente espressa da Heinrich Wölfflin nella prefazione ai suoi Prolegomeni a una psicologia dell'architettura2, scritto nel 1886 dall'autore appena ventiduenne come dissertazione inaugurale alla Facoltà di Filosofia dell'Università di Monaco: "come è possibile che delle forme architettoniche siano espressione di un'anima, di una Stimmung"?

Dunque il problema è questo: è ancora possibile oggi prendere in considerazione le risorse comunicative degli ordini architettonici per produrre significati attraverso l'architettura?1 L. Quaroni, Progettare un edificio. Otto lezioni di architettura, Gabriele Mazzotta editore, Milano 1977, p. 215.

2 H. Wölfflin, Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur, 1886. French edition: Wölfflin, Prolégomènes à une psychologie de l’architecture, introduction by Bruno Queysanne, Editions Carré, 1996. -

Orders in Architecture. Do Architectural Forms Have a Meaning? (eng)

Vol. 3 No. 6 (2015)ORDERS IN ARCHITECTURE. Do Architectural Forms Have a Meaning?

The issue of the "orders" in architecture covers an extremely vast field of theories, studies and design experiences that have all been developed in the framework of the architectural thinking of the Western tradition.

The classical architectural orders established a stylistic canon, a code, and a language as well, in order for architectures to speak, to transmit and to signify.

Generally speaking, the core issue is the creation of meanings through architecture.

In this view, a major vehicle of sense has not just been the experience of architectural orders, but rather their transgression, their variation, up to the extreme end of disorder. Following Ludovico Quaroni, "The Greeks, the Etruscans, the Romans, the architects of the Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque, Classicism made use of the orders to design as many architectures, and these were different, and even opposite one versus the other. [...] The orders were only components of the architectural design, that is, elements drawn from manuals that could be used and transformed in relation to the various syntactic contexts"1.

The issue of the architectural orders is therefore a partial answer to a broader question, skilfully phrased in 1886 by the twenty-two years old Heinrich Wölfflin in the introduction to Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur2, his inaugural dissertation at the Faculty of Philosophy of Munich University: "How it is possible that architectural forms are an expression of soul, of a Stimmung"?

Therefore, the question is: is it still possible today to refer to the communicative resources of the architectural orders for creating meanings through architecture?1 L. Quaroni, Progettare un edificio. Otto lezioni di architettura, Gabriele Mazzotta editore, Milano 1977, p. 215.

2 H. Wölfflin, Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur, 1886. French edition: H. Wölfflin, Prolégomè¨nes à une psychologie de l'architecture, introduction by Bruno Queysanne, Editions Carré, 1996. -

L'ADC UNESCO-Chair "Sustainable Urban Quality" Series#1 (eng) - Asmara, an urban history

2014This publication defines the culmination of a doctoral thesis, focusing on the urban history and development of the city of Asmara (Eritrea). The thesis had been written with the aim of tracing the history of the urban evolution of the city of Asmara in order to identify its morphology, which had been generated by both planned and unplanned urban spatial development.

The first part of the book discusses the urban development knowledge of Asmara before 1941, in a historical and logical discourse, within an analytical framework comprising the following components: population, geography, and history of the place. However, the main focus of this study is the second part, which connects the colonial development of the city with the contemporary form, from 1941 to 2005.

Asmara was generated at the beginning of 1500 A.D., emerging from the union of four villages that was collectively known as Arbate Asmera, and the city started to develop as an urbanized settlement since the end of the nineteenth century A.D. From about the year 1893, the bulk of the city developed along the infrastructure and urban planning principles of the Italian colonial administration. During this administration, urban planning in Asmara was closely related to that of Italian cities and to the urban features and principles of Western urban planning. At the end of Italian colonialism in April ’41, Eritrea fell under British administration, which reigned until 1952, during which time there were no processes of urban planning, despite the city continuing to grow organically. This situation persisted even during the years of Federation (1952-1962) and annexation (1962-91) in Ethiopia.

To understand the development of an organic urban plan of the city during recent past decades, reference must be made to the beginning of the 70s, during which time a new Master Plan for Asmara was conceptualized and developed by the Siena-based architect Arturo Mezzedimi. The Town Plan of the Mezzedimi Firm represented the last comprehensive plan for the city of Asmara.

The thesis concludes by establishing the origins and precursors to the contemporary city of Asmara. It was found that urban development planning was stagnant during the three decades following the 70s, and any new planning would only start to materialize in 2005, primarily through the initiatives of the Government of Eritrea and international consulting firms. This realized the development of “The Strategic Urban Development Plan, and the Identification of Priority Projects” document, accompanied by a Strategic Plan and an outline of Urban Planning Regulations. These documents were sourced and synthesized to inform a true general plan of the entire Greater Asmara Area, representing the new beginning of the city. The historic links in the evolution and development of the city of Asmara, in Eritrea, are thereby established.

Like any city, Asmara, a young city even by the standards of young African capitals, is a stage set where the drama of history has unfolded in the most intense and eloquent manner. The territory of Asmara stands at the edge of a space of almost mythical civilizations, ancient religions, and proud empires. It is also a natural acropolis in the vastness of Africa, an astoundingly high crest that looks down from above on the coast of the “Eritrean” sea, coming to a halt where the Afar Rift expands and, year after year, rips into the heart of Africa where lions and gnus still roam free. However, in its body, and thus in its history, Asmara is also a fragment of Europe, imported atop the undulating highlands of Hamasien by the presumption of the most fragile and thus most presumptuous of colonial nations: Italy. Less than 130 years later, history appears to have intentionally concentrated a host of events, projects, interests, delusions, conflicts, and hopes in Asmara that, within the vaster expanses of historical time, could have filled dozens of centuries. These metamorphoses were like immense waves lapping at a resistant soil, introducing and withdrawing diverse foreign armies, peoples, languages, cultures, and adversities. The results of so much labor have forged the identity of Eritrea, jealously defended for decades and jealously guarded to this day. Looking carefully in libraries among printed works dedicated to particular aspects of this identity—numerous and some very important—it is impossible to find a history of Eritrea that is scientifically complete and up-to-date. This is a serious shortcoming. Yet everything has remained impressed upon the land, and even more eloquently, on the city, on the face and limbs of Asmara. Hence the reconstruction, like that made by the author of this book, of the difficult process of planning the city signifies not only restoring, like an animation, the history of the complex growth of an urban organism.

Lucio Valerio Barbera

UNESCO Chairholder in “Sustainable Urban Quality and Urban Culture, notably in Africa,” Sapienza Università di RomaAt the end of the Thirties, from Naples to Massawa (the “Port of Empire,” since 1890 an important commercial base and natural access point for anyone wishing to reach Asmara and the Eritrean uplands), the voyage took five days; from the port, one could reach the capital of the Colony by train, on an intrepid mountain railway, or by a motor road, Road No. 1 from Dogali—as Asmara was only 120 km away. If one wanted to make the journey by air, it took three and a half days, thanks to the “Empire Line,” which involved taking a seaplane from the Carlo Del Prete base in Ostia to Benghazi in Libya, and then a plane to the Umberto Maddalena Airport in Asmara, with stops at Cairo, Wadi Halfa, Khartoum, and Cassala on the Sudanese border.

And right next door to the Airport stood the Teleferica Massawa-Asmara, an extraordinary cableway for transporting goods up onto the plateau at a height difference of 2,326 meters; the cableway had been built in two years, between 1935 and 1937, and at a length of 75 km, was the longest industrial cableway system in the world. It could move in one day the equivalent of thirty train loads, but it was at its full operational capacity for only a few years: in 1941 it was damaged in the war with the British, and ten years later, when Eritrea became a British Protectorate, it was unexpectedly decided to dismantle it.

These events act as a backdrop and form a solid framework for Tecle Misghina’s research—which is not only meticulous but emotionally involved—of which this book is a well-documented summary. Her research is important in that it reconfigures and puts in order various documents, both known and unpublished, to build a chronology and a set of references indispensable for anyone wishing to carry out further studies on the Eritrean capital. For a project developed within a Doctoral program, this is, in my opinion, the most important outcome of her research.

Piero Ostilio Rossi

Director of the Department of Architecture and Design, Sapienza Università di Roma -

L'ADC Monograph Series#2 (eng): Five Easy Pieces dedicated to Ludovico Quaroni

2014Five easy pieces dedicated to Ludovico Quaroni

Monograph by Lucio Valerio BarberaIn every style: "... At that time we were young and possessed of fixed ideas, and for us the name Quaroni was associated with three things that were far removed from the idea of modernity, an idea we reckoned was worth fighting and scheming for. First there was the village of "La Martella", with its cultivated, pedantic pattern of little peasant farmers [...] Then there was the Olivetti-inspired movement "Comunità", to which we knew Quaroni had to some extent subscribed to [...] Thirdly, there was the “Tiburtino†residential district; when I visited it, I got the impression that it was an obvious showcase for provincial affectation; anything but part of a modern city.

Charisma: Quaroni was sitting next to De Carlo, and had raised his upper body, leaning over the table as if it was some massive slab of rock; he had listened to De Carlo's address humbly and attentively, following every word. Now his face took on a different expression; he frowned, his brows knitted, his chin tucked in. Slowly, he uttered a single sentence: "Asserting my prerogative as Chairman of this Seminar, I reserve the right not to speak." Not to speak. A murmur greeted his statement.

Schubert was stupid: A few weeks later I went to visit Ludovico in his studio where he was finding room for a large stack of records; he had piled them up on a chair next to his record-player, and the stack was wobbling dangerously. I don't remember exactly why I had gone to see him, but even at the time I soon forgot the reason; I hurried to help him with this enormous pile of music, and my curiosity was aroused “I had myself only a meager stock of records and a great desire to hear more.

Elective misunderstandings: Quaroni had had a flash of fondness when I had told him about my coming journey to Milan and my visit to the BBPR studio. "Give Lodovico my best wishes (Lodovico with an "o" not with a "u" like me). I haven't seen him since he was teaching in Venice. I'd really like to get in touch with him again. Just think... I met him in 1938 in EUR. Or was it 1939? ...

Letzte Lieder: All the Lieder composers, then, have objectively speaking written their last songs, their Letzte Lieder. But for most music lovers "last song" means above all the Vier Letzte Lieder, the "˜Four Last Songs", for soprano and orchestra, by Richard Strauss, written in 1947 when the composer was eighty-three years old. Music critics are agreed that Strauss, in his old age, had regained his full creative powers; the music shrouds the words in a vibrant atmosphere of melancholy, and the last song of all is pointedly entitled Im Abendrot: "In the Twilight". We would all like to see our own Master do likewise.

-

L'ADC Monograph Series#1 (ita): Architettura Integrata

2013Architettura Integrata

Monografia di Wu LiangyongIntroduzione di Lucio Valerio Barbera

Traduzione di Anna Irene Del Monaco, Liu Jian, Ying Jin, George Michael Riddel, Roberta Tontini

Postfazione di Anna Irene Del MonacoIl libro che presentiamo, Architettura Integrata è¨ un testo storico e attuale. Fu pubblicato nel 1989 da Wu Liangyong, uno dei più¹ influenti architetti e maestri di pensiero della Cina contemporanea col titolo A General Theory of Architecture. Egli è¨ figura eminente della comunità internazionale degli architetti e, soprattutto, di quel gruppo di teorici dell'architettura e della città che si battono per una decisiva riforma delle concezioni, delle metodologie e delle prassi che presiedono alla costruzione e alla riqualificazione della metropoli contemporanea. Conobbi il professor Wu Liangyong nel 2004 nella Facoltà di Architettura della università Tsinghua di Beijing; la sua Facoltà. Egli nel 1946 aveva 24 anni ne fu il fondatore assieme a Liang Sicheng, il padre dei moderni studi sull'architettura cinese. Da allora sono passati sessantasette anni il professor Wu Liangyong mantiene il suo ruolo di figura centrale della comunità accademica di Beijing, ed un costante stimolo, non solo a livello nazionale, per il rinnovamento degli studi, e, soprattutto, della ricerca teorica, metodologica e operativa sull'architettura, la città , il territorio, dunque, una figura rara, che ha attraversato per intero un periodo storico che in ogni luogo del mondo è stato tumultuoso per la società e la città , ma che in Cina ha forse avuto le sue manifestazioni più drammatiche ed esaltanti; un periodo fatto di guerra, di speranze, di rivoluzioni, di slanci, di presunzioni, di orrori, di errori, di nuovi slanci e d'incomprimibile crescita economica; di irreversibili metamorfosi sociali e culturali e a ciò che qui, per noi, conta di più di travolgenti crescite urbane e trasformazioni territoriali. Nella sua figura minuta e gentile il suo intelletto ha resistito saldissimo alle tempeste della storia traendo dall'osservazione degli eventi e dai principi umanistici e scientifici della propria cultura, il continuo alimento per una riflessione sempre più¹ efficace sul significato dell'architettura nel mondo attuale, sul suo intreccio inestricabile con la sostanza della città; e sull'insostituibile ruolo dell'architetto, scienziato, umanista ed artista. Pochi anni dopo aver averlo conosciuto e aver iniziato ad apprendere direttamente la sua opera di architetto e di teorico, gli proposi di tradurre in italiano un'antologia di suoi scritti, tratti dai tanti libri e saggi sull'architettura e la città pubblicati con continuità durante tutta la sua impareggiabile carriera. Egli mi rispose rilanciando: al posto dell'antologia di scritti propose di tradurre per intero, in italiano e in inglese, un libro di venti anni prima, appunto A General Theory of Architecture del 1989. Data la velocità attuale del dibattito culturale si sarebbe detto si trattasse di un libro ormai sedimentato nella storia. Compresi, invece, che si trattava di una pietra miliare per l'espressione del suo pensiero; un caposaldo da cui, probabilmente, erano scaturite le sue elaborazioni teoriche posteriori, anche quelle più¹ recenti, pubblicate in altri fondamentali saggi, che spaziano nel vasto campo degli insediamenti umani toccando tutte le componenti dell'mbiente antropizzato (Lucio Valerio Barbera).

As Architect, urban planner and teacher, Wu Liangyong has played a very significant role in China over the last several decades and has been a source of considerable influence and inspiration to generations of Chinese architects, making them aware not only of the new architectural spirit that was taking root elsewhere in the world, but also of the sublime beauty (and ingenious invention) so manifest in China's own traditional architecture – and how the life-long endeavour, reinforce by the oeuvre of work he has created in his own professional practice – including housing projects right in the heart of Beijing that are wonderful re-inventions of the low-rise high density courtyard typologies found in traditional Chinese habitat. Besides all this, Professor Wu is a wonderfully gifted artist. In fact, when I first met him he had a sketchbook and was happily recording mountains, buildings and people – all in a few masterful strokes. Today with the range and depth of his invaluable contributions, Wu Liangyong occupies a truly unique place in the architectural scene of China. Charles Correa, Architect, Royal Gold Medal RIBA (1984)

Professor Wu Liangyong, a pioneering philosophical architect, who in his century has the qualities Confucius must have been thinking of in 500 B.C., when he said "humility is the solid foundation of all virtues". Rod Hackney, Past President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and International Union of Architects

è altamente significativa la consonanza fra gli intenti del libro Architettura Integrata di Wu Liangyong, architetto, e il pensiero del fondatore della Facoltà di Architettura di Roma, Gustavo Giovannoni, ingegnere, che fin dal 1916, nel saggio Gli Architetti e gli studi di architettura in Italia, si espresse a favore di una figura di "architetto integrale", tecnico, artista, conoscitore della storia dell'architettura. E poi quasi sorprendente come il programma e i contenuti del libro Architettura Integrata nei fatti concordi con il programma e i contenuti della formazione dell'architetto che lo stesso Gustavo Giovannoni espresse, nel 1920, nella prolusione del primo Anno Accademico della nuova Scuola Superiore d'Architettura in Roma: una formazione basata sulla costante sperimentazione dell'integrazione operativa e intellettuale tra la coscienza artistica, la coscienza storica e la coscienza strutturale del costruire; ciò in cui crediamo e che ci caratterizza ancora oggi. Renato Masiani, Preside della Facoltà di Architettura, Sapienza Università di Roma

Conobbi il professor Wu Liangyong presso la Facoltà di Architettura della Sapienza in occasione del Convegno di Studio Housing and Cities nel 2006. Fui ammirato del fatto che il professor Lucio Barbera fosse stato in grado di portare alla Sapienza l'allievo e il continuatore del grande Liang Sicheng, il professor Wu Liangyong, che per tutti noi, non solo architetti, è un eminente rappresentate della cultura moderna cinese. Il libro Architettura Integrata, pubblicato per la prima volta in Cina nel 1989, fu redatto in anni cruciali in cui fui diretto testimone del clima culturale, esaltante e complesso, dell'intera Cina e di Beijing in particolare. Lo slancio culturale di quegli anni, le speranze, l'intuizione del ruolo che le città avrebbero avuto nell'evoluzione della società cinese, ma anche la visione delle grandi innovazioni culturali e di metodo necessarie per affrontare il futuro, tutto ciò vive appassionatamente nelle pagine di questo libro. Sono lieto, pertanto, che la nostra ex Facoltà di Studi Orientali, attraverso l'opera di traduzione della dottoressa Roberta Tontini, abbia contribuito alla traduzione in italiano di questa straordinaria opera del professor Wu. Federico Masini, Professore di lingua e letteratura cinese, Sapienza Università di Roma

Le pagine del libro A General Theory of Architecture (Integrated Architecture) del professor Wu Liangyong ci insegnano molte cose: ad avere fiducia in una formazione aperta, curiosa e duttile, ad indagare i territori di frontiera tra le diverse discipline e a confidare nella loro fecondità nel campo della ricerca. Ne ho molto apprezzato l'approccio trans-disciplinare che ci spinge ad assumere all'interno del progetto urbano anche i punti di vista specifici di altre discipline poiché sono convinto che solo questo metodo possa produrre soluzioni convincenti e durature nel tempo. Piero Ostilio Rossi, Direttore del Dipartimento di Architettura e Progetto, Sapienza Università di Roma

It is hard to think of anyone in whose works grandeur of vision and pathos are so profoundly intermingled as those of Professor Wu Liangyong. For almost seventy years Professor. A quarter century after its first publication, viewed across China's endless urban sprawl and environmental degradation, Integrated Architecture seems both wise and naive. Like the writings of Constantinos Doxiadis, Christopher Alexander, and Andres Duany, it strives to place the architect at the center of a vast synthesis of human knowledge, grants him the possibility of understanding the relationship of virtually everything to virtually everything else, then makes him the actor who will bring the wisdom of this synthesis to the making of the world. How doomed. How noble. Daniel Solomon, Professor Emeritus of Architecture and Urban Design UC Berkeley

-

L'ADC Monograph Series#1 (eng): Integrated Architecture

2013Integrated Architecture

Monograph by Wu LiangyongForeword by Lucio Valerio Barbera

Translation by Anna Irene Del Monaco, Liu Jian, Ying Jin, George Michael Riddel, Roberta Tontini

Afterword by Anna Irene Del MonacoÂ

Integrated Architecture is both a historical and contemporary work. The book was first published in 1989 by Wu Liangyong, one of contemporary China's most influential architects and theoreticians with the title A General Theory on Architecture. His eminence is also recognised by the international architectural community, above all, the group of architectural and urban planning theoreticians battling for a more decisive reform to the concepts, methodologies and practices presiding over the construction and requalification of the contemporary metropolis. I first met professor Wu Liangyong in 2005 at the Faculty of Architecture at the Tsinghua University of Beijing; his Faculty. Wu Liangyong founded the school in 1949 "at the age of 24“ together with Liang Sicheng, the father of modern Chinese architectural studies. From this moment “ more than sixty-seven years ago “professor Wu Liangyong has remained a central figure in Beijing's academic community. He remains a constant source of inspiration, not only national, to education reforms and, above all, theoretical, methodological and operative research into architecture, the city and the territory. He is a rare figure, present throughout a lengthy historical period witness the world over to tumultuous upheavals in society and its cities. A period whose most dramatic and exalting manifestations were perhaps to be found in China; a period of war, of hope, of revolutions, of great leaps forward, of presumptions, horrors, errors, new leaps forward and incomprehensible economic growth; of irreversible social and cultural metamorphoses and “what interests us most as architects“ of staggering urban growth and territorial transformations. The intellect of this minute and genteel figure held fast against the storms of history. The observation of events and the humanist and scientific principles of his personal culture continuously nourished an increasingly more effective reflection on the meaning of architecture in today's world. He also clearly saw its inextricable ties to the substance of the city and the impossibility to substitute the figure of the architect “ scientist, humanist and artist. A few years after our meeting, having absorbed direct lessons from Wu's work as an architect and theoretician, I proposed an Italian translation of an anthology of his writings. The material was to be drawn from his many books and essays on architecture and the city published continuously over the course of his incomparable career. Professor Wu Liangyong responded with a challenge: in lieu of this anthology of texts he proposed a full translation, in Italian and English, of a book published twenty years ago: 1989's A General Theory on Architecture. Given the pace of cultural debate it would not have been out of place to imagine a book firmly sedimented in history. I understood, instead, that it was a milestone in the expression of Wu Liangyong's ideas; a benchmark that, in all likelihood, served as the starting point for his later theories, even the most recent. Published in other fundamental essays, they range across the vast field of human settlements, touching on all components of the man-made environment (Lucio Valerio Barbera).

As Architect, urban planner and teacher, Wu Liangyong has played a very significant role in China over the last several decades and has been a source of considerable influence and inspiration to generations of Chinese architects, making them aware not only of the new architectural spirit that was taking root elsewhere in the world, but also of the sublime beauty (and ingenious invention) so manifest in China's own traditional architecture “and how the life-long endeavour, reinforce by the oeuvre of work he has created in his own professional practice“ including housing projects right in the heart of Beijing that are wonderful re-inventions of the low-rise high density courtyard typologies found in traditional Chinese habitat. Besides all this, Professor Wu is a wonderfully gifted artist. In fact, when I first met him he had a sketchbook and was happily recording mountains, buildings and people “ all in a few masterful strokes. Today with the range and depth of his invaluable contributions, Wu Liangyong occupies a truly unique place in the architectural scene of China. Charles Correa, Architect, Royal Gold Medal RIBA (1984)

Professor Wu Liangyong, a pioneering philosophical architect, who in his century has the qualities Confucius must have been thinking of in 500 B.C., when he said "humility is the solid foundation of all virtues".

Rod Hackney, Past President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and International Union of Architects

There is a highly indicative correspondence between the aims expressed in Integrated Architecture by Wu Liangyong, who is an architect, and the way of thinking of Gustavo Giovannoni, who was an engineer and the founder of the Faculty of Architecture in Rome, and who, as far back as 1916, in his paper Gli Architetti e gli studi di architettura in Italia, gave his support to the idea of a "complete architect", who would be a technician, an artist, and have a full knowledge of the history of architecture. And then it is quite extraordinary how the plan of action and the contents of Integrated Architecture correspond in actuality to the programme and contents involved in the training of an architect which Giovannoni set out in 1920 in his inauguration of the first academic year of the new School of Architecture in Rome. An architect's education was to be based on a regular analysis of the functional and intellectual interaction between artistic and historical awareness and the structural knowledge of how to build; something we believe in and that defines us even today. Renato Masiani, Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Sapienza Università di Roma

I met Wu Liangyong in the Faculty of Architecture of Rome Sapienza University during the Study Conference "Housing and Cities" in 2006. I was impressed by the fact that Professor Lucio Barbera had managed to bring to Sapienza university the pupil and heir of the great Liang Sicheng, professor Wu Liangyong, who for all of us, and not only for architects, was a distinguished exemplar of modern Chinese culture. His book, Integrated Architecture, first published in China in 1989, was written during the pivotal years in which I directly experienced the complex, exciting, cultural climate prevailing throughout China, and in Beijing in particular. The enthusiasms and hopes expressed in those years, the realisation of the role that the cities had played in the evolution of Chinese society, but also the understanding of the great cultural innovations taking place and the approaches that were needed to face the future, all these were passionately alive within the pages of the book. I am also grateful that our ex-Faculty of Oriental Studies, with the translation work of Roberta Tontini, has had a part in the translation into Italian of Professor Wu's remarkable book. Federico Masini, Professor of Chinese Language and Literature, Sapienza Università di Roma

The book A General Theory of Architecture (Integrated Architecture) by Wu Liangyong teaches us many things: to have faith in an open-minded, curiosity-founded, flexible form of education, to explore the borderlands between different disciplines and to trust that such territories will prove fertile ground for research. I value highly the book's cross-disciplinary approach which, within the context of urban design, prompts us to accept specific viewpoints from other fields of study, since I am convinced that this is the only approach that can allow us to reach solutions that are reliable and long-lasting.

Piero Ostilio Rossi, Director of the Department of Architecture and Design, Sapienza Università di Roma

It is hard to think of anyone in whose works grandeur of vision and pathos are so profoundly intermingled as those of Professor Wu Liangyong. For almost seventy years Professor Wu has been the voice and the conscience of the Chinese City. A quarter century after its first publication, viewed across China's endless urban sprawl and environmental degradation, Integrated Architecture seems both wise and naive. Like the writings of Constantinos Doxiadis, Christopher Alexander, and Andres Duany, it strives to place the architect at the center of a vast synthesis of human knowledge, grants him the possibility of understanding the relationship of virtually everything to virtually everything else, then makes him the actor who will bring the wisdom of this synthesis to the making of the world. How doomed. How noble. Daniel Solomon, Professor Emeritus of Architecture and Urban Design, UC Berkeley

-

Ludovico Quaroni the Architect (eng)

Vol. 1 No. 1-2 (2013)Ludovico Quaroni, romano, è stato un maestro dell'architettura italiana nella seconda metà del Novecento. Il suo magistero ha contribuito a formare non solo gran parte delle giovani generazioni di architetti italiani, ma anche figure come Carlo Aymonino, Manfredo Tafuri e Antonino Terranova. Inoltre, è stato uno dei riferimenti fondamentali per l’elaborazione teorica di Aldo Rossi sulla città.

Architetto e urbanista, docente e scrittore, Quaroni rappresenta lo sperimentalismo metodologico e linguistico più aperto e inclusivo, nonché l’aspetto più progressivo dell’identità dell’architettura italiana moderna. La sua opera si fondava su un saldo rapporto tra cultura storica, sensibilità sociale e contestuale, competenza scientifica del progetto e una appassionata esplorazione del futuro, caratterizzata da coraggio e libertà creativa.

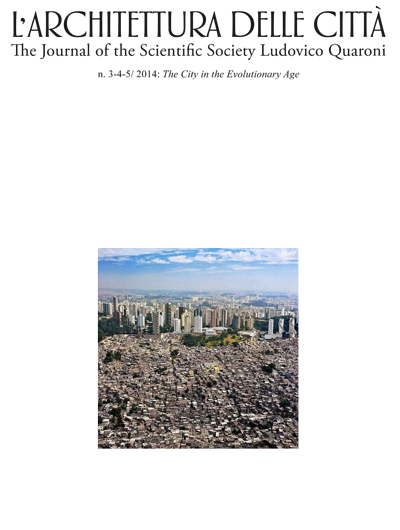

Adottando il suo nome, la Società Scientifica, con la rivista che qui presentiamo, intende rilanciare la discussione sull’Architettura delle Città in un momento in cui metodologie, tecnologie, rapporti tra le scale progettuali, significati e linguaggi formali e simbolici delle città—tutto ciò di cui la moderna cultura urbana occidentale sembrava per un attimo sicura—appaiono oggi travolti dalla vertigine dell’espansione urbana più rapida e imponente della storia dell’umanità, che coinvolge tanto i continenti più antichi quanto i più nuovi.

-

Ludovico Quaroni l'Architetto (ita)

Vol. 1 No. 1-2 (2013)Ludovico Quaroni, a native Roman, was a master of Italian architecture during the second half of the twentieth century; his talent contributed to the education in addition to the majority of the younger generations of architects in Italy as Carlo Aymonino, Manfredo Tafuri and Antonino Terranova. He also constituted one of the fundamental references to the elaboration of Aldo Rossi's theories on the city. An architect and urban planner, professor and author, Quaroni represents the most open and inclusive methodological and linguistic experimentalism and the most progressive identity of modern Italian architecture, founded on the close relationship between historic culture, social and contextual awareness, a scientific understanding of design and a passionate investigation of the future; courageous and unbridled. In adopting his name for the review presented today, the Scientific Society intends to return to the discussion of the Architecture of Cities at a time when methodologies, technologies, relationships between the scales of design, the formal and symbolic meanings and languages of the city, everything about which modern Western urban culture appeared certain, now appear overrun by the vertiginous nature of the most rapid and imposing urban expansion in human history, sweeping across both ancient and new continents.